Even though the world of special effects has become a platform for technical wizardry, it still requires a number of elements to achieve the desired impact. Whether it’s sound or visual effects, many elements are mixed and connected to create an effect that is one step beyond. It’s part of the production culture. It always has been.

Many decades ago, sound and visual special effects people relied on combinations to create different worlds, or, in some cases, simulate the world as it was. In Part 2 of a look at special effects, we remember and are dazzled b the talents of those who did not have the benefit of digital tools.

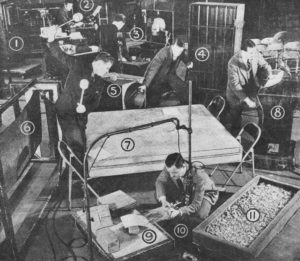

RADIO (and sometime, sound effects for film)

Back in the 1920s, there was only one way to capture sound: the microphone. The manifestation of simple effects required true ingenuity in the application of physical things required to emulate other physical things.

Drop a grand piano’s lid and you created a big door closing. Crunch corn flakes in a cardboard box and, voila, footsteps in the snow. Take a match stick and snap it — baseball bat hitting a ball. Grab a drumstick and hit the edge of a drum and you’re in the middle a gunfight. Alternatively, the effects person could use two wooden boards and clap them toget6her to invoke the same effect.

Another favourite used in both radio and the theatre was the huge metal sheet. Bending and snapping it at the right moment emitted a crash followed by rolling thunder — instant lightning.

In Monty Python’s film, Holy Grail, King Arthur leads his knights on a search for the coveted Grail. In one of the first scenes, we hear the sound of horses off screen. Entering frame, we see the brave knights knocking coconuts together as they skip their way along the path. It was not a new idea. Coconuts were a favourite source for clopping hooves in radio dramas focused on the Wild West.

As technology advanced in the early phase of radio, the turntable began to play a larger role in sound effects generation. An automobile engine or some larger motor used in industry would be recorded and printed to disc. Not only would it be used to paint the mental picture of a car, but the record could be sped up to emulate acceleration.

Further to that, using copies of the record with various turntables would, for example, multiply the number of cars in a race. Using the volume control, it was easy to replicate the sequence of cars (or even horses) approaching from a distance, entering the scene and fading back into the distance. As a footnote, combustion engines were very effective in producing a waterfall effect.

To round out the list of other manual effects produced: running finger nails along the edge of a comb produced crickets; blowing through a straw into water — boiling water; rubbing swords or foils together — skating; squeezing folded sandpaper — eggs breaking; twisting a leather wallet — getting on or off a saddle.

Fast forward to today. Even in the digital age, creating a unique sound still requires ingenuity. Interestingly enough, the lightsaber effect in Star Wars required an old movie projector motor. The humming sound of the motor together with the interference of a television set on a shieldless microphone served as the basis of the iconic effect.

If you want to experiment with manual sound effects, Gamesradar offers a superb how-to guide.

MOVIE EFFECTS

E.T National Film and Sound Archive

Where to begin? Certainly, the flying bicycle sequence in E.T (Spielberg) is at the top of the contemporary list. The sequence was filmed on one of Hollywood’s largest blue screen studios along with massive rigging equipment to capture the flight of the children over the city. The rest was digital — a science too broad to delve into. However, it is interesting to note that the blue screen has been changed to green screen as a result of the high definition cameras in use today.

Perhaps the most recent and significant advance in digital visual effects (as agreed upon by many who write bout effects) is the making of Gollum, that crafty and vulnerable character in “Lord of the Rings”, truly a precious one. It set the stage for further effects created for “Avatar” and “Rise of the Planet of the Apes”.

They called the technique “combination sculpting”, now referred to as “motion capture” or “mo-cap”. The actor, Andy Serkis, wore a tight, greyish unitard fitted with hundreds of sensors on the body and face. These movements were captured digitally and, from there, CGI artists built everything on the character and eventually into the scenes.

To cap off this brief look at special effects, we go back to the parting of the Red Sea in the film “The Ten Commandments”, a 1956 Cecile B. DeMille epic starring Charlton Heston.

It required miniatures, pyrotechniques, travelling matte paintings, and a 32-foot water tank (to produce the waterfall). The real trick was to run the dumping of the water tank footage in reverse. You can watch this Oscar winning effect here.

So there’s a brief look at special effects. It is still true that, even with the arsenal of digital capabilities at an artist’s fingertips, some of the best effects start with ordinary things. It might be said that it takes things not so special to transform reality with special effects.

If you want to enjoy a deep dive into the history of special effects, check out Richard Rickett’s “Special Effects: The History and Technique”.

If you’d like to start playing with your own special effects, check out the Special Effects section at ShopProductionWorld.com.